As we near an age in which interfaces are primarily touchscreen, it is important to question whether the

nuances of this technology are convenient for all.

Visiting a local assisted living facility through the duration of a class called Design for the Aging Population, I was able to collect first hand information about senior attitudes towards touchscreen. I used my research to prototype a tablet case that provides haptic feedback and physical button alternatives to screen interactivity.

observation

Holding and Hovering:

The thin ipad appeared difficult to grip with one hand. The residents rarely supported the device with two, instead keeping their tapping hands suspended above the ipad while considering a next action.

Stabilizing and Positioning:

The ipad was seldom operated from a user's lap. Some residents chose not to freehandedly hold the machine and propped it against their bodies. Cushioned armrests appeared to provide convenient vertical positioning, despite their lack of frontality.

Tapping and Swiping:

Residents in their 80s and 90s had the most trouble interacting with the screen. Tapping inaccuracies were followed by high pressure presses and lost interest. The pictured resident, an arthritis sufferer, curled his fingers slightly and used his middle finger to move digital checkers during our game.

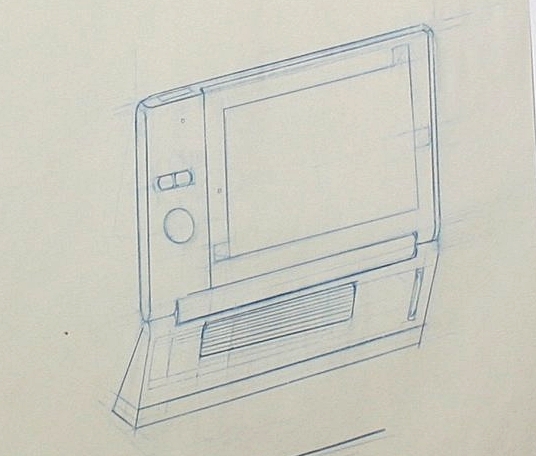

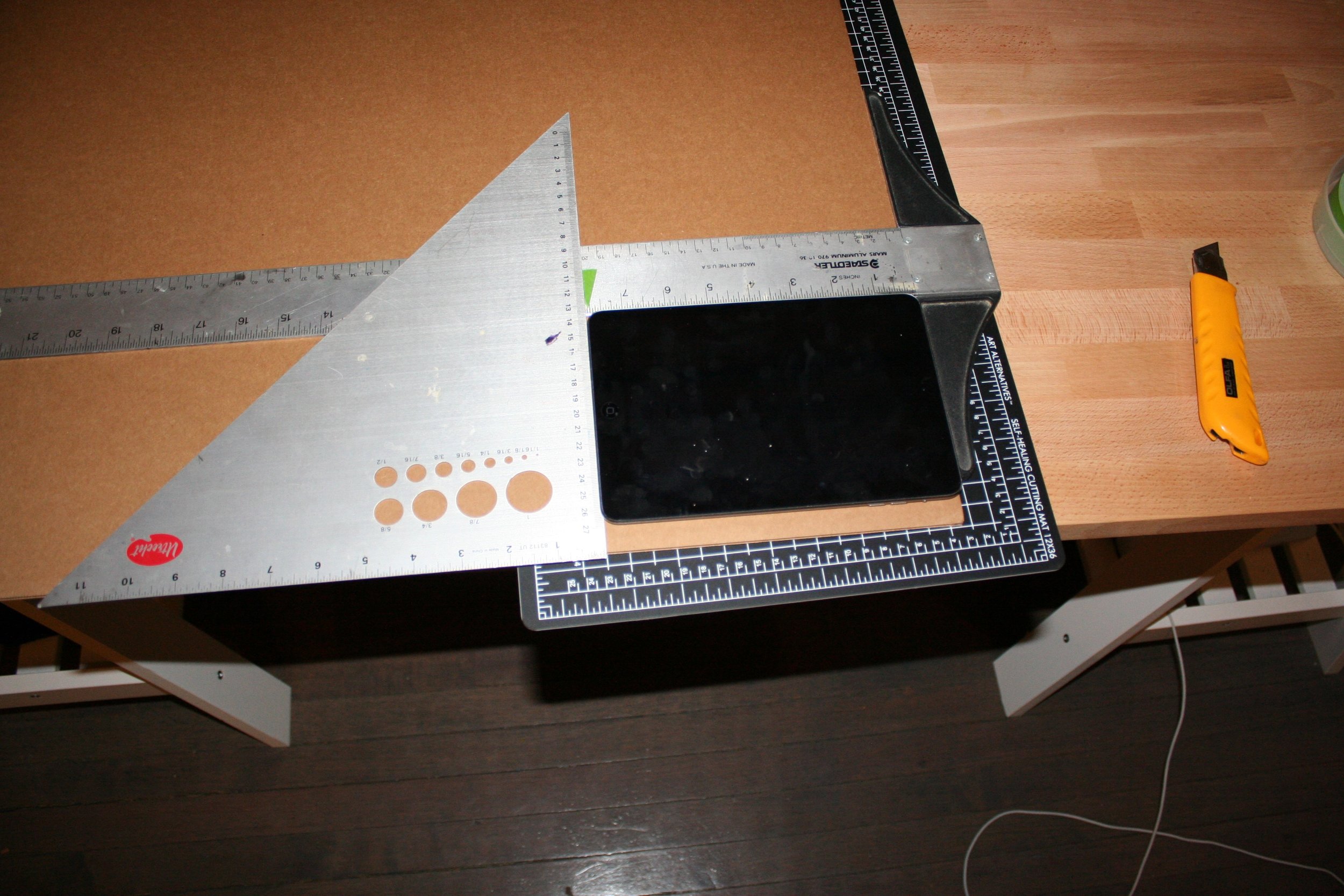

Giving form

I created a series of paper and foam prototypes for tablet cases, imagining that a taller model might be advantageous as it would allow a user to easily support the device with one hand and easily angle it in different positions to optimize his or her view.

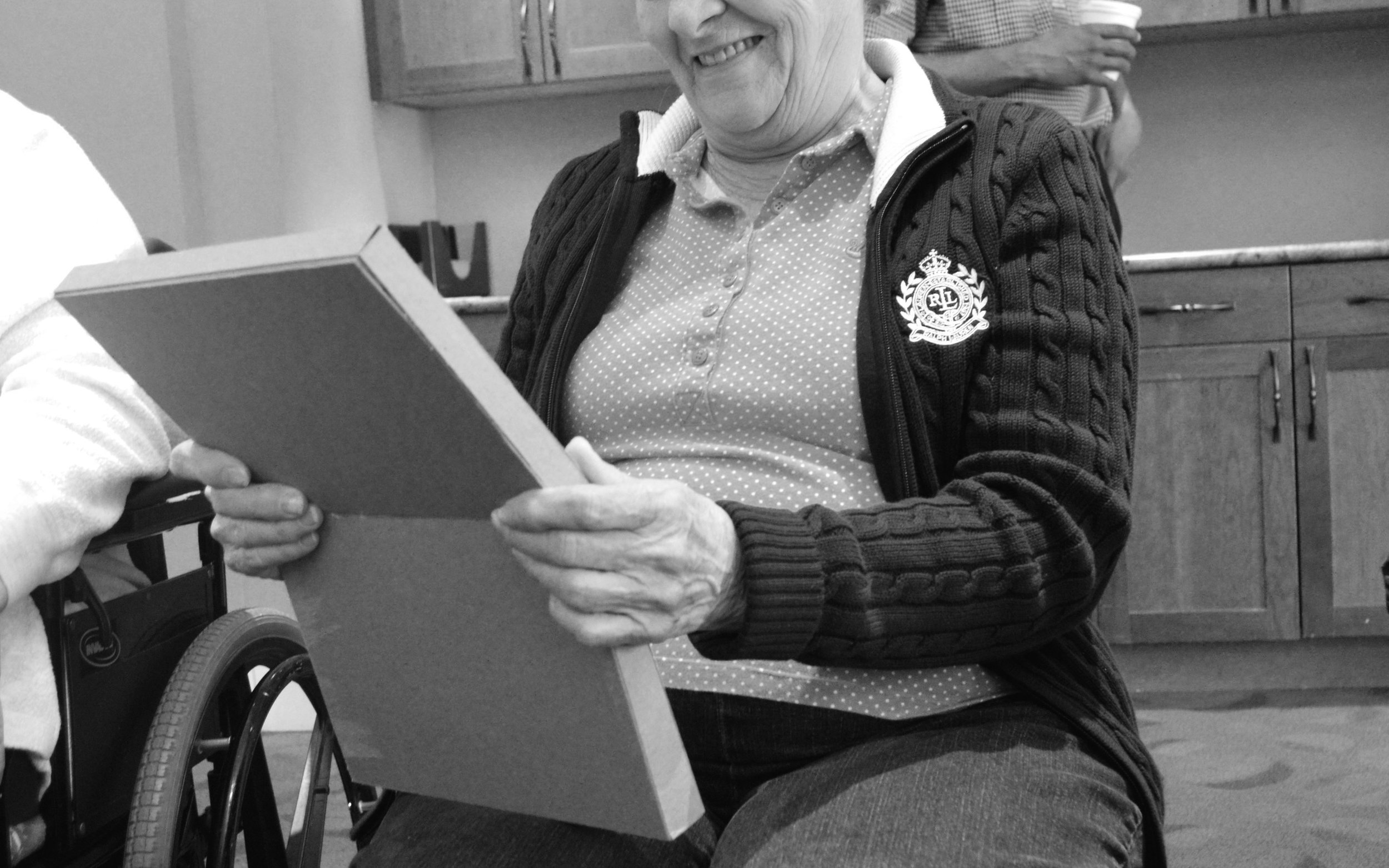

user testing

The residents did look more comfortable holding the paper prototype that I had constructed. But, they were not satisfied

with it's size.

Some noted that they appreciated the sleek look of my ipad and felt that it's elegance would disappear into my large design. So, I reconsidered my original model. After many more form studies, I produced a squat muff-like stand with a removable screen. The form provided an adequate amount of elevation for table or lap usage and presented a comfortable place to rest ones hands.

considering touch

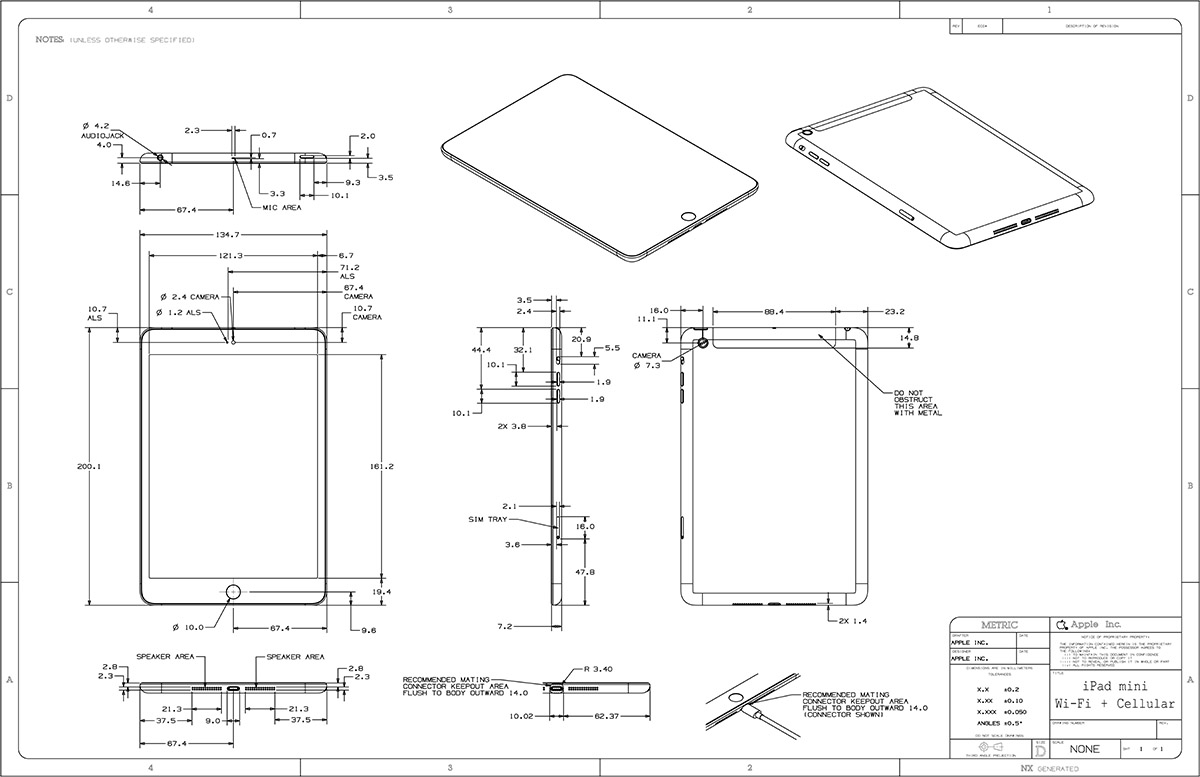

I speculated that additional physical escape routes would benefit the aging population and added six buttons to my model.

The physical buttons on an ipad are camouflaged into it's form. However, they provide important alternatives to touchscreen activity at times when a device is malfunctioning,

when rapid control is necessary, or when a user can't locate an on-screen button.

Finally, I set out to change the tactile experience of touchscreen manipulation. I brainstormed about forms that might slip over one's finger, or slide across the screen. However, the notion of adding a separate, moving part to the device seemed less than satisfactory. It might get lost and it introduced baggage into an experience I intended to make streamlined and intuitive.

I wondered if it might be possible to implant the auditory and tactile feedback of a computer mouse within a touchscreen. The definitive click of a mouse would provide concrete feedback as to whether or not a tap registered with the device. Further, accidental taps would be less likely as more pressure would be required to effectively select a target.

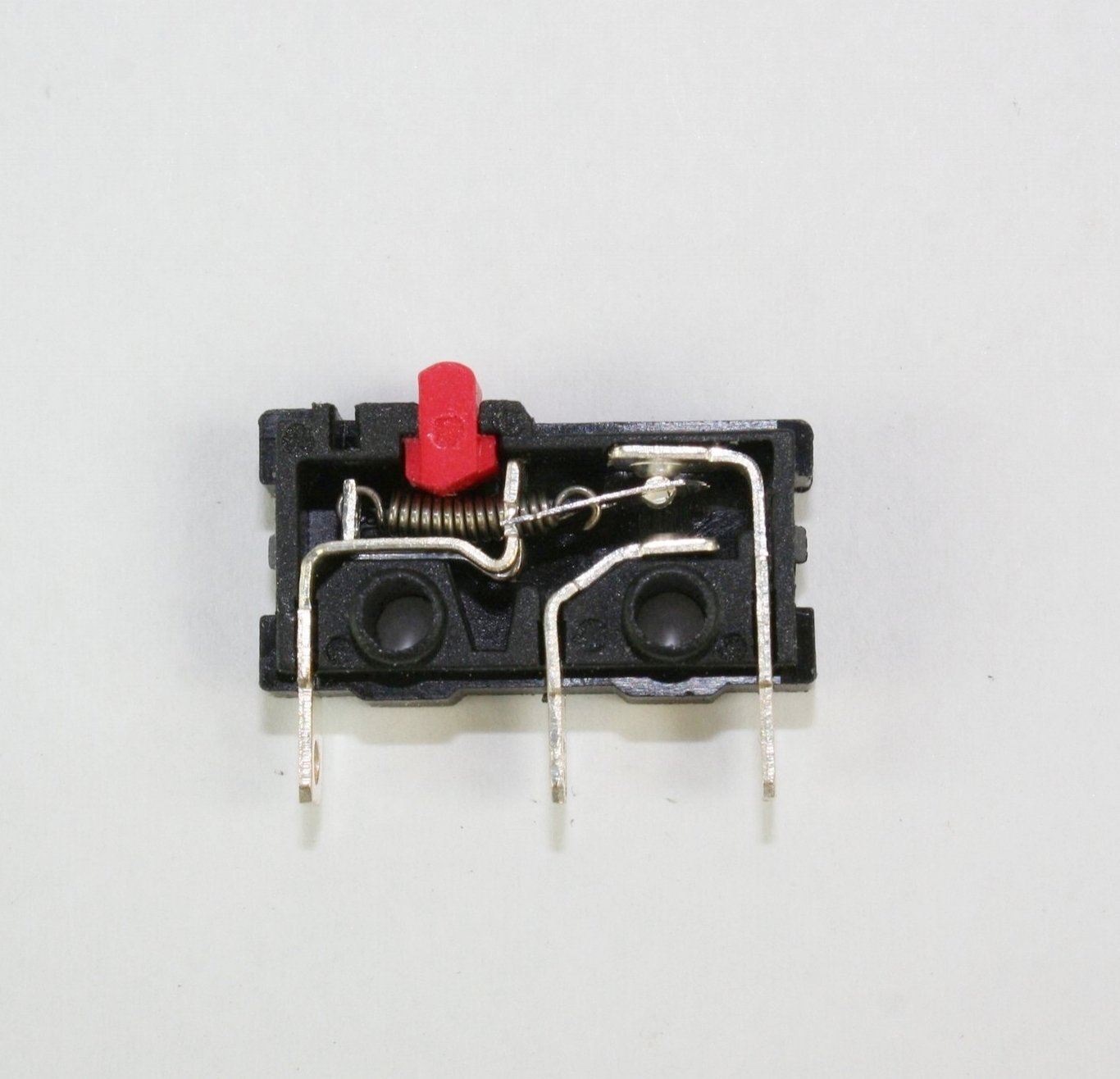

I took apart a computer mouse and studied the mechanics of the microswitch that causes it's satisfying click. I then implanted microswitches behind an ipad within my final model so that the experience of clicking a screen might be more understandable to my users and design audience.